Myanmar is geopolitically important for China, principally to boost its strategic presence in the Indian Ocean, to reduce the transport time for some of its trade, and to achieve the objective of its long-term “two-ocean” master plan. Thus, China needed to choose the right strategy after the military coup in Myanmar on 1 February 2021 to ensure a continued relationship.

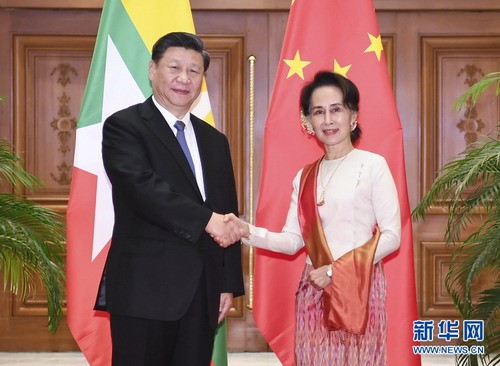

PRC President Xi Jinping during official talks with the now deposed and jailed State Counsellor of Myanmar Aung San Suu Kyi in 2020

Due to Beijing’s initially ambiguous attitude towards the coup, the PRC government did not favor the Myanmar military but, despite having a reasonable relationship with Aung San Suu Kyi, the civilian leader, it did not favor the protest movement either. Nevertheless, remaining neutral was not an option in the long term considering all the possible political and other costs.

Immediately following the coup, Beijing was extremely cautious in its comments about what had happened in Myanmar. While other countries expressed serious concern and denounced the military’s actions, China merely noted the situation and turned a blind eye to the coup. Indeed, to avoid having to ‘pick a side’, China opposed the UN Human Rights Council’s calls for the release of Aung San Suu Kyi, insisting that this was Myanmar’s ‘internal affair’ and, as such, should not be interfered with. When thousands of people took to the streets in Myanmar to join peaceful protests and were shot at by the military, various countries and international organizations, especially the European Union and the G7, issued statements demanding that the military refrain from violence against demonstrators. The United States, Great Britain, and Canada announced sanctions on the junta leaders and several companies only a few days after the coup, and the EU did so the following month. Countries such as Japan, India, and Australia called for the return of democracy in Myanmar. China remained silent.

China’s initial reservations towards the situation in Myanmar were also reflected in Chinese media reports. Official Chinese state-run media (such as Xinhua or People’s Daily), which is directly controlled and monitored by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and whose tone and reporting directly reflect the government’s attitude, referred to the coup as a ‘cabinet reshuffle’, avoiding the word ‘coup’ altogether. However, while official state media downplayed any mention of the violence that occurred in the wake of the coup, Chinese local media outlets targeting Chinese audiences were less hesitant. Large newspapers not directly owned by the CCP (such as Southern Weekly or Beijing News) described the military takeover as a coup. Domestically, the long-term objective of such reporting is to maintain China’s power, and reporting on the ‘undemocratic’ misery of foreign countries strengthens the government’s legitimacy by increasing the relative satisfaction felt by its citizens towards their national environment. Internationally, however, the government chose to be more reserved to optimize its international leverage.

Since the image of China in Myanmar has been severely damaged for a long time (as a result of China providing economic, military, and diplomatic support to previous dictators in return for access to Myanmar’s natural resources), and Beijing did not adopt a firm stance on the Myanmar coup in the initial weeks, it is not surprising that China was accused of being involved in the coup. As a result, many rumors circulated on the internet—for example, that Chinese soldiers were present on the streets of Myanmar. This culminated in a protest against China in April 2021 and the Chinese flag being burned in Yangon.

In the months following the coup, various Chinese assets in Myanmar were attacked. In March 2021, dozens of Chinese-financed factories in Yangon were assaulted and some were even destroyed by arson. In May 2021, guards at the Mandalay offtake station of the oil and gas pipelines that link Myanmar's deep-water port in the Bay of Bengal with China were killed. In June, a bomb exploded at a Chinese clothing factory in the Ayeyarwady Region. In January 2022, electricity pylons supplying a China-backed nickel-processing plant in the Sagaing Region were blown up. Chinese officials condemned all these attacks and urged the authorities in Myanmar to prevent any further violence to ensure the safety of Chinese citizens and Chinese-owned businesses. The coup leader, Min Aung Hlaing, reassured Beijing that his regime would protect foreign-funded enterprises. China’s reaction to the attacks—blaming the protesters and only mentioning financial damage without considering the people killed by the junta—further angered Myanmar’s pro-democracy movement.

From its initial ambiguity, China moved to officially supporting the efforts of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to assist Myanmar, basically using the association as a proxy. China emphasized the principle of non-interference in other countries’ internal affairs and promoted restoring stability ‘the ASEAN way’.

While China also made contact with Myanmar’s parallel government (set up after the coup to counter the illegally established junta), it nonetheless edged closer and closer to the recognition of Myanmar’s military regime, having previously avoided explicitly picking a side. As time passed and the likelihood of the civilian government returning to power diminished, it became more geopolitically beneficial for China to embrace friendly relations with the newly established military regime.

After the coup/junta leader met the Chinese ambassador in Yangon, an embassy’s Facebook statement identified him as the ‘Leader of Myanmar’. Chinese state-run media followed suit.

China’s leaning towards the military junta was confirmed in June 2021 when the junta was invited to several events, including the third Belt and Road Initiative meeting, the special ASEAN–China Foreign Ministers meeting, and the Mekong-Lancang Cooperation meeting. At these events, several projects to be implemented in Myanmar were approved, for which millions of dollars were to be transferred from the Chinese government to the Myanmar military. China also assisted the junta with the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines, donating millions of doses.

In 2022 and 2023, this trend in the development of China–Myanmar relations has persisted. Although Myanmar’s military has continued to face domestic resistance and struggled to consolidate its power, Beijing has grown closer to the military regime.

The full version of this article will be published in 2023 as: Kironska, K., and D. Jiang, 2023, “China-Myanmar Relations After the 1 February Military Coup”, in Ware, A., and M. Skidmore, After the Coup: Myanmar's political and humanitarian crisis, Canberra: ANU Press.

by Kristina Kironska (Assistant Professor at Palacky University Olomouc and Advocacy Director at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies) and Diya Jiang (PhD Candidate at McGill University in Canada)

August 2023

Source: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/2020zt/xjpdmdgsfw/202010/t20201019_698684.html